The Albatross: Majesty in Peril

With “Effects of Disease” as the focus of this year’s World Albatross Day, microbial ecologist Dr Meagan Dewar examines the threat of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) across the Antarctic – and the coordinated effort to protect the region’s vulnerable Southern Ocean species.

With wings that stretch wider than any bird on Earth – up to a staggering 12 feet (three-plus metres) – the albatross is more than just a marvel of the skies. These enigmatic emblems of Southern Ocean exploration are built for endurance, gliding across oceans for hours without flapping their wings, and disappearing from land for months – sometimes even years – at a time. And with lifespans that can rival humans, the albatross can seem almost mythical.

But behind their almost supernatural grace lies a grim truth: many albatross species are inching dangerously towards extinction.

Every year on June 19, we mark World Albatross Day – a global event born out of a commitment made in 2001 with the signing of the Agreement for the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) by 13 party nations. This isn’t just another commemorative calendar entry – it’s a call to action. Each year, the day highlights a specific threat these birds face. In 2025, the spotlight lands squarely on a formidable and fast-moving adversary: disease.

This year’s theme, “Effects of Disease,” focuses on two endangered species: the Amsterdam Albatross and the Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross, both of which breed on remote sub-Antarctic islands. Their already precarious existence is being further rattled by a rising global menace: High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI).

You may have caught wind of it in the news – an aggressive strain of bird flu that’s devastating avian populations across the globe. But HPAI isn’t just a far-off problem. It was confirmed in the sub-Antarctics in 2023 and the Antarctic Peninsula in 2024, marking significant and sobering milestones in the virus’s global spread.

Carried by infected migrating birds, it threatens the regions’ iconic residents, including penguins, albatrosses, skuas, and Antarctic terns. Unlike earlier strains, this version spreads faster, hits harder, and doesn’t stop at birds – it’s been infecting Elephant seals and fur seals too.

The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) has taken this threat seriously - very seriously – from the beginning.

IAATO, in collaboration with the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) and the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP), has stepped up to fortify its already stringent biosecurity protocols. These are more than guidelines; they are mandatory actions to safeguard Antarctic wildlife and visitors alike. Here’s what’s happening in the field:

- Eyes wide open: Before any visitor sets foot on a landing site, trained staff assess for signs of illness in wildlife. If anything looks off, they are prepared to cancel the visit.

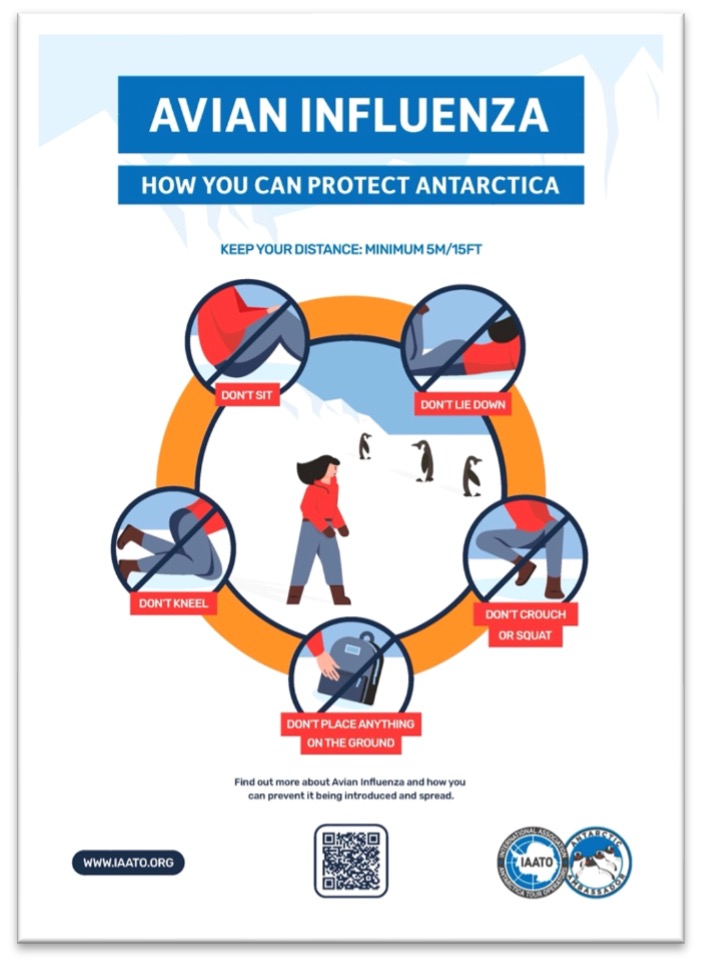

- Keep your distance: A minimum distance of 5 metres (15 feet) between visitors and Antarctic wildlife is non-negotiable.

- Let wildlife come to you? Not quite: If animals approach, you must back off – but do it safely.

- No lounging allowed: Visitors must not sit, kneel, crouch, lie down, or leave gear on the ground or snow near animal activity, such as colonies, pathways, haul-out sites.

- Every visit counts: Any concerning behaviour or sign is reported to IAATO, which consults with experts to explore next steps.

Beyond the field, IAATO Members are contributing to the bigger picture. From funding research expeditions that track the spread of HPAI in Antarctica to sponsoring the 11th International Symposium on Avian Influenza, held in Newfoundland, Canada, next week, the commitment runs deep.

Because saving the albatross isn’t just about one bird; it’s about preserving an entire web of life that spans the Southern Ocean and beyond.

Want to take action?

Visit the ACAP website to learn more about World Albatross Day and discover how you can help protect one of the planet’s most majestic – and most threatened – creatures.

About the author | Dr Meagan Dewar of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research's Antarctic Wildlife Health Network (SCAR-AWHN)

Dr Meagan Dewar specialises in host-microbiome interactions and pathogens of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic wildlife. She has a PhD in Microbial Ecology of Seabirds and is a Lecturer in Biological and Environmental Sciences at Federation University. Meagan’s research focuses on investigating the interactions between wildlife and microorganisms in relation to host health, physiology and nutrition. Meagan is also the co-chair of the Antarctic Wildlife Health working group.