Isolation Salvation: A Polar Scientist's Guide to Staying Sane During Lockdown

From the Heroic Age of Exploration to modern day scientists conducting research on Antarctica’s ice-sheets, isolation is part and parcel of polar science and discovery. Not only is Antarctica remote, but when winter sets in, the sun ceases to rise and flights in and out of Antarctic bases closest to the South Pole become impossible, leaving scientists and researchers over-wintering on the white continent until spring, isolated, thousands of miles from home and far from those they love.

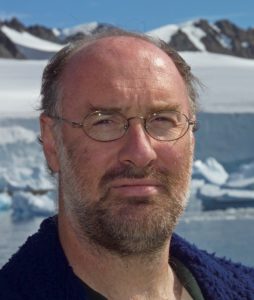

With a career with the British Antarctic Survey spanning more than three decades, with long months of polar isolation under his belt, we turned to terrestrial ecologist and Antarctic over-wintering veteran Peter Convey for his top tips on how to stay sane when there’s nowhere to go...

Peter in Finlandia Foothills, northern Alexander Island, Antarctica in 2018

Peter in Finlandia Foothills, northern Alexander Island, Antarctica in 2018

1. Be realistic about timescale

Sitting under forms of 'lockdown' your automatic thought is 'this will never end', and however long it is, May, July, September, or next spring can easily feel a very long way away. I recall, as we went into our winter, about to see the last ship leave, I sat on a local headland with people who'd only been there for a short summer, had done a winter, and had done two winters, but all due to leave at that point. All were very ready to leave, and all were equally sure their very different times on our isolated island had in some sense rushed past - time doesn't drag if you don't let it.

Rather than focusing on tomorrow, with the largely unspoken but widespread hope of 'something will change', think of this situation as the new normal and if you think of any timescale, make it one of months ..... sounds hard initially, but if you can do it, you may well almost forget about thinking of the passage of time.

2. 'Normal' is where you are and what you are doing

We each have our own sense of normal and normality. What we are doing now, and have now been doing for some time, is now what is normal for us. The more we divert ourselves with thinking that it is unusual, or unknown, the more likely we are to be in some way frightened of it and even to panic - and for most people, most of the time, there is absolutely no reason to do that.

3. Don’t underestimate the power of routine

It’s good practice to maintain some form of daily and weekly routine; make the effort to get up by a certain time, and be in bed by a certain time, and have a plan for the different things you might do each day and as time goes by. That doesn't mean follow it blindly and rigidly - you can reward yourself with the odd lie in, a late night up, or whatever else floats your boat - and don't do exactly the same thing every day. Variety helps.

What you can do obviously depends where you are, what risk category you are in, whether you have something like a garden or an outside area you can safely exercise in some way, etc, but whatever you can do, do it.

4. Eating is important (!)

When you're in any form of isolation, and particularly when you are physically restricted, mealtimes can become the highlight of the day. It's also good for your health to eat regularly, and not to excess, and to the best of your ability to manage a varied and healthy diet.

Many of us might be doing more actual cooking than we’re accustomed to, which itself is no bad thing as it's an enjoyable and satisfying thing to do, as well as a learning exercise. In fieldwork, you can easily be stuck physically inside your tent for several days, even weeks in a bad period, and the main meal of the day (usually in the evening for us) is a real focus and highlight. Believe me, British Antarctic Survey field food will win no culinary prizes, but is specially designed to give us all the nutrients we need.

It can take several hours to cook the meal of the day in the field, not because of the food itself, but everything you have to do around it, and boy does dinner taste good when you finally get it.

So, eat regularly, and make at least some of your meals special events, where you put deliberate effort into preparing them, and enjoy having them, whether you're alone, with a partner or family – whatever!

5. It’s good to talk...

This is far easier today than it was when I wintered or during my earlier summer field seasons in Antarctica. In those days most communication was by HF radio. There was no email or web, and although our stations had the first generation of satellite telephones largely for emergencies, they cost a whopping £7-9 (almost $9 – 11 USD) per minute to make a call! So we did it as little as possible; Christmas and major family birthdays, and the days of those calls were the worst of days while you were there....you never said what you wanted to in the way you wanted, and often all it did was distress you and those you called.

Nowadays there are many ways to stay in touch, so make use of them! It doesn't need to be long and deep conversation, though sometimes it can be. Often a short hello, couple of questions about how your contact is, do they need anything, exchanging a few photos or anecdotes is all that is needed.

Most of us have quite a few social media contacts; family and friends from the various parts of our lives. Make a point of fairly regularly, but fairly randomly, catching up with some of them, messages, voice calls, video chats etc. If you do have access to the traditional postal service, it's amazing how nice it is for most people to receive a physical card or letter, even if it sounds like something out of the history books to the younger generation.

When I am in the Antarctic, and indeed travelling almost anywhere (in recent years I've spent around a third of the year away from home) I usually manage to post a few postcards to my wife and various friends around the world. They arrive a few weeks to many months later, and seem to be very well received, and stimulate further conversations themselves.

What are your tips for keeping it together during self-isolation? Join us on Facebook to share your pearls of wisdom.

About the author | Prof. Peter Convey

About the author | Prof. Peter Convey

Peter Convey is a terrestrial ecologist and self-proclaimed 'glorified natural historian' who loves to enthuse about the natural world. He has more than 30 years of experience of working with the British Antarctic Survey and in a wide range of polar environments (19 Antarctic summers and one winter, and multiple Arctic including Svalbard, Greenland, Russia) field or teaching periods. He has broad and diverse research interests, with over 390 publications, including:

• Biodiversity and biogeography of polar terrestrial invertebrates, plants and microbes; • Life history and ecophysiological strategies of polar terrestrial biota; • Polar ecosystems as models of the past and future global consequences of climate change; • Palaeobiogeographical reconstruction of Antarctica; • Human impacts, conservation and management in Antarctica.