Visualising the Invisible: The Hidden World of the Western Antarctic Peninsula

We all expect to see charismatic penguins and majestic whales on the Antarctic Peninsula, but these waters are teeming with life that we don’t even notice because of their microscopic size.

Sometimes biologists count more than three million organisms per litre of water! How many kinds can we find in Antarctic waters? Many!

After each Antarctic summer season, I receive small bottles of sea water collected by travellers participating in the FjordPhyto citizen science project – if you want to know more about this project read Tiny But Mighty.  Each time visitors collect a bottle of sea water and preserve the samples with a special dye, it’s like taking a snapshot in time; “freezing” the organisms that are floating in the ocean in that moment. The dye does not allow for new organisms (like bacteria) to grow, so samples can be preserved, before being safely transported to the Universidad Nacional de La Plata in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where I work. I then spend time in my lab examining each sample under the microscope.

Each time visitors collect a bottle of sea water and preserve the samples with a special dye, it’s like taking a snapshot in time; “freezing” the organisms that are floating in the ocean in that moment. The dye does not allow for new organisms (like bacteria) to grow, so samples can be preserved, before being safely transported to the Universidad Nacional de La Plata in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where I work. I then spend time in my lab examining each sample under the microscope.

I calculate how many organisms are in a litre of water, recording what species are present, and what quantity of organic carbon the organisms represent; meaning, how much energy is available for the bigger animals to eat. When I compare my results from the many samples, I can see how this diversity changes over the season, who is replacing whom from November to March.  Microorganisms in the water come from very different evolutionary lineages and have very different strategies for living. I look for tiny microalgae; organisms that drift in the water but photosynthesize like plants. Scientists call these drifting microalgae phytoplankton - krill food, and Antarctic krill is food for all the animals living in Antarctica, such as whales, penguins, seals, and more.

Microorganisms in the water come from very different evolutionary lineages and have very different strategies for living. I look for tiny microalgae; organisms that drift in the water but photosynthesize like plants. Scientists call these drifting microalgae phytoplankton - krill food, and Antarctic krill is food for all the animals living in Antarctica, such as whales, penguins, seals, and more.

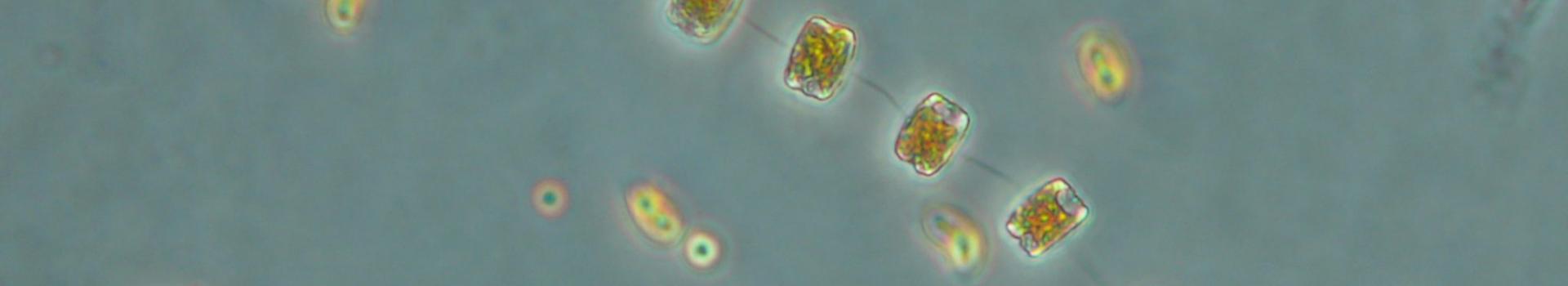

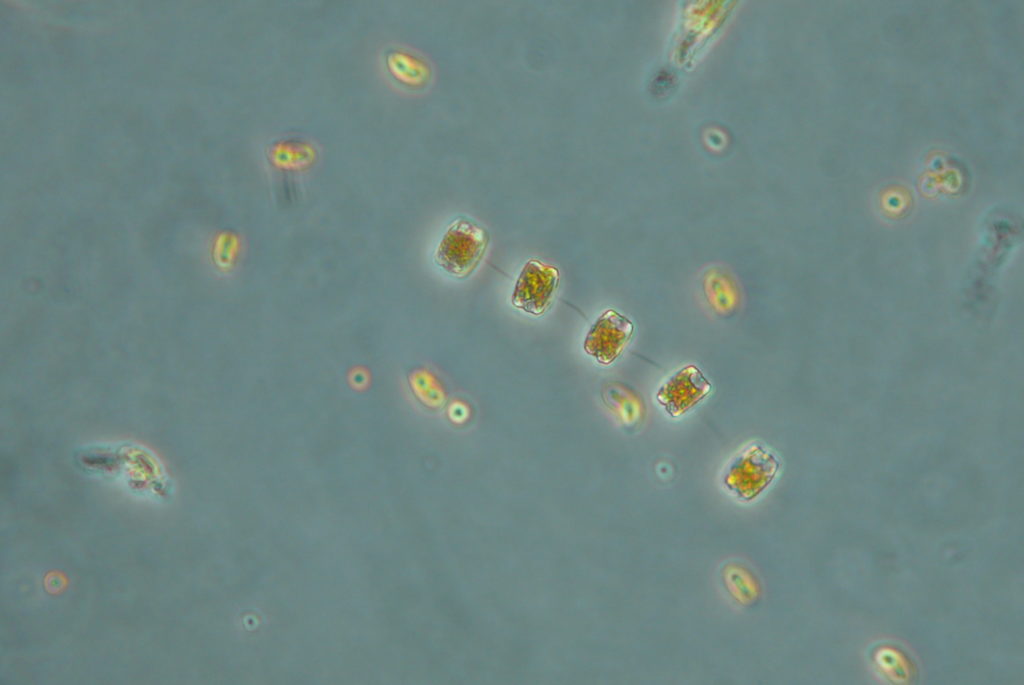

I have found many different phytoplankton in water samples and taken high-resolution pictures of them. My favourites are called diatoms; individual single-celled organisms that live inside of a silica box, like a house of glass. These silica boxes are really intricate and very well designed, and come in a lot of different shapes. Different shapes allow these organisms to live in different ways.

Diatoms have been living on the Earth for more than 190 million years - that’s a lot of time to evolve to perfection. This is why they can be found in almost every place on the planet. Diatoms in Antarctic waters are very important; they are the krill’s favourite food and they play a key role in the ecosystem and global cycling of carbon. Diatoms photosynthesize like plants, so they absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. This organic carbon is transferred through the food web, released back into the atmosphere, or sinks to the depths. In other words, after they die the cells carry the carbon to the sea floor.

Due to the global biodiversity crisis we are currently going through (scientists call it the Earth’s sixth mass extinction event), it is essential to record all the organisms found in these waters. The coastal areas along the Antarctica Peninsula, where IAATO member operators help sample phytoplankton with visitors through the FjordPhyto citizen science project, have no previous records of microalgae, so my microscopic records are the baseline for future comparisons to show changes in composition due to climate change, e.g. loss of biodiversity.

My work is also important because I record the biodiversity and figure out how much carbon is entering the ecosystem through these tiny microorganisms. Thanks to the samples collected by IAATO operators participating in FjordPhyto, I know that the largest quantities of organic carbon can be found at Neko Harbor, Cuverville and Danco Islands. In addition, the samples that I analyze are deposited in the phycology collection of the Natural Museum of La Plata for future examination.

I am currently collaborating with Celeste Kroeger, a Chilean researcher, designing a photo identification book of phytoplankton from the Antarctic Peninsula. This book is for non-scientific audiences and will be an outreach effort that future visitors can use on their Antarctic expeditions as they observe water samples under the microscope on board IAATO vessels. This resource has many ecological and interesting facts about the different species of phytoplankton living in the Antarctic together with microscopic pictures of all of them taken by me and lovely hand-drawings by Celeste.

About the Author | Martina Mascioni

Martina Mascioni is a PhD student of the Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (Argentina) under her advisors’ supervision, Dr. Gastón Almandoz at the Phycology Division and Dr. Maria Vernet at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego, USA. In 2019, Martina was awarded with IAATO-COMNAP and SCAR fellowships to travel to California and collaborate with Dr Vernet and Allison Cusick, also at Scripps. Due to the pandemic, her travel is currently on hold until international travel is deemed safe and available. Although Martina has a vast knowledge of the white continent, she had never been there! She hopes to join a cruise ship to work with FjordPhyto in the field next season.

Martina was born in Ushuaia, Argentina, one of the cities that most tourists visit before or after their trip to Antarctica. She lived there until she was five years old and then she moved with her family to San Luis, a city in the centre of the country. When she was 18, she moved to La Plata city to pursue a scientific career as a biologist. In 2016 she was granted the degree of Bachelor in Biology with honours and the next year started with her PhD thesis focused on the ecology and taxonomy of the phytoplankton of the coastal zones (fjords) of the western Antarctic Peninsula. Martina is passionate about her work with microalgae and although she is finishing her PhD thesis in a couple of years, she hopes to keep working on polar phytoplankton for many more to come.