Women's History Month: Shining a Spotlight on Antarctica's Female Firsts

The history of Antarctica is dominated by the stories of extraordinary men like Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and Robert Falcon Scott but as Dr Joanna Kafarowski points out in her blog earlier this month, literature about polar women remains woefully sparse.

To continue our Women’s History Month celebration, we’re sharing seven biographies of awe-inspiring polar women that have made undeniable contributions to the frozen continent.

Abby Jane Morrell – U.S.

Abby Jane Morrell was an American traveller and author known for writing the first account of a sub-Antarctic expedition from a woman's perspective.

Her adventure began in early 1824 when Abby was just 15 years old. She became reacquainted with her cousin, Captain Benjamin Morrell, whom she had not seen in a decade. After several weeks of courting, the two were married. Just days later, Abby's new husband set off on a two-year voyage. She wrote, “I knew when I married him that I was to be the wife of a sea-faring man, but it was impossible for me to realize the distress of separation.”

During one of her husband’s several European voyages (1825-1828), Abby had a son. Shortly after the birth, Benjamin left for what Abby referred to as the “South Seas”. Abby found this separation to be even more challenging than before, and she was determined to travel with her husband on his next voyage. He agreed, and when they set sail in 1829, their son was left in the care of Abby’s mother. “I knew he was in good hands, but he was not in my own; I knew my dear mother would do everything for him that I could, but nothing will satisfy a mother in regard to her offspring, but her own care," she wrote.

On September 2, 1829, the Morrells set sail on Benjamin's schooner, Antarctic. From 1829 to 1831, they sailed around the world to the Cape Verde Islands, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Liberia, South Africa, and the Kerguelen Islands (Desolation Islands). They even visited the same harbour as Captain James Cook, the British explorer and naval officer who was the first to cross the Antarctic Circle in 1773. Abby described these sub-Antarctic islands as:

“No place in either hemisphere hitherto discovered, affords a better field for a naturalist than this. The seabirds are numerous, including several kinds of albatrosses – a greater variety than I ever saw before; they were so thick around the vessel that they were in each other’s way. Seals and sea-elephants were once numerous here also.”

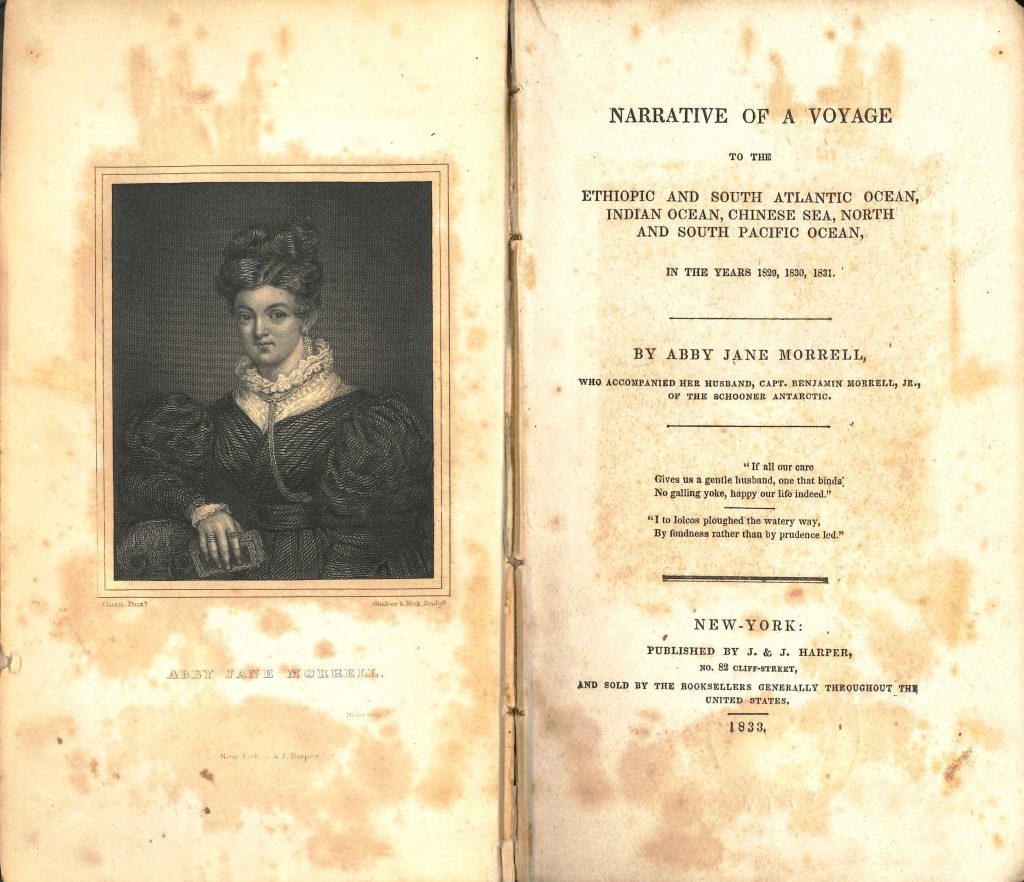

Following their trip, both Abby and Benjamin published accounts of their travels. Abby's book, Narrative of a voyage to the Ethiopic and South Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Chinese Sea, North and South Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1829, 1830, 1831 (1833), was the first description of the sub-Antarctic written by a woman. This was her only book, and sadly, there is little documented history of her life after 1838. Records dated 1841 and 1850 suggest she was in New York. Her death is estimated to be around 1855.

Learn more about Abby’s life from her book, Narrative of a Voyage.

Abby Jane Morrell's portrait and the title page of her book. Source: Reed Gallery'S (N.Z.) "Treasury of Pacific Exploration - Voyaging Literature from the McNab Collection" Exhibit.

Abby Jane Morrell's portrait and the title page of her book. Source: Reed Gallery'S (N.Z.) "Treasury of Pacific Exploration - Voyaging Literature from the McNab Collection" Exhibit.

Ingrid Christensen – Norway

Ingrid Christensen (1891- 1976) was a polar explorer and widely regarded as the first women to set foot on the Antarctic mainland. She was the first woman to see and fly over Antarctica.

Ingrid was born in 1891 to Alfhild Freng Dahl and Thor Dahl, an influential ship merchant. At the age of 19, she married Lars Christensen, and this marriage united two of Sandefjord’s most powerful ship-owning families.

Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance was originally built for Lars Christensen, but Christensen decided to sell it to Shackleton despite his own desire to see Antarctica.

During the 1930s, Lars Christensen sailed to Antarctica many times, and Ingrid travelled with him on at least four occasions. Notably, she sailed there with her husband on the Thorshavn in spring 1931 accompanied by her friend, Mathilde Wegger. Australian geologist and explorer Douglas Mawson even saw the women during his British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE). After seeing them, he wired back a report to the Australian media:

“On one occasion, emerging from a belt of sparkling pack, we came upon two vessels lying side-by-side, coaling in a calm ice-girt pool. This prosaic business provoked little interest but as we drew near enough to distinguish those on board, much astonishment was excited by the dramatic appearance on their decks of two women attired in the modes of civilisation. Theirs is a unique experience, for they can make much merit of the fact that they are, perhaps, the first of their sex to visit Antarctica.”

Ingrid sailed to Antarctica again in 1933, 1933-1934, and 1936-1937. In 1933, she sailed with Lillemor Rachelew, who kept a diary and took photographs which Lars later published in his account of the expedition. However, they did not land on the Antarctic continent. Ingebjørg Dedichen, another Norwegian shipping heiress, sailed with the Christensens on their 1933-34 expedition. During this trip, their ship circumnavigated most of the frozen continent.

Ingrid's final expedition in 1936-37 included her daughter Augusta Sofie Christensen, and friends Lillemor Rachlew and Solveig Widerøe. On January 30, 1937, Ingrid set foot on Antarctica at the Scullin Monolith, and today, she is widely regarded as the first woman to stand on the Antarctic mainland. She was also flown over the frozen continent, making her the first woman to see Antarctica by air.

The Ingrid Christensen Coast in East Antarctica was named to honour her accomplishments, and the Four Ladies Bank in Prydz Bay, East Antarctica was named to commemorate Ingrid's expedition with her daughter, Lillemor, and Solveig.

Ingrid Christensen and Mathilde Wegger on voyage in 1931

Ingrid Christensen and Mathilde Wegger on voyage in 1931

Nel Law – Australia

Artist and poet Nel Law (1914-1990) became the first Australian woman to set foot on Antarctica on February 8, 1961.

Nel's husband, Dr. Phillip Law, was a scientist and the director of the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) from 1949-1966. He travelled to Antarctica for five months at a time annually. After 12 years at home while her husband explored the frozen continent, the couple decided it was time they explored together.

Phillip helped Nel stow away on Magga Dan, a Danish icebreaker ship, to Mawson Station. It was standard practice for Danish captains to include their wives on long voyages, but not common in Australia. Nel was discovered before the Magga Dan set sail, but was allowed to stay onboard to avoid the anticipated media backlash her removal would cause. Other Australian women were not officially allowed on ANARE expeditions until 1976.

While in Antarctica, Nel painted a series of over 100 abstract oil and watercolour paintings. These paintings are even more impressive when considering that she could only work on them in the warmth of the ship where her supplies would not be frozen solid. She took extensive notes and memorised the colours she saw to create her stunning works. Nel also illustrated one of the early ANARE logos, which was used as a stamp design and released in 1954.

Nel Law's 1961 oil painting "Penguins on Ice Floe" Source: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via ABC News Australia

Nel Law's 1961 oil painting "Penguins on Ice Floe" Source: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery via ABC News Australia

To commemorate her accomplishments, the Australian government named a new supply vessel after her in 1961. The Nella Dan ship was the most famous of the Danish ANARE ships. She sailed for 26 years until 1987.

In 1965, Nel founded the Antarctic Wives Association of Australia, now known as the Antarctic Family and Friends Association, which "is a support and social group for family and friends of current and former expeditioners".

Nel passed away in 1990 at age 75 and Phillip in 2010. According to Australian Antarctic Division Director Lyn Maddock, Phillip’s final wish was to be interred alongside other expeditioners who died in Antarctica, so his and Nel’s ashes were transported to back to the region on the Aurora Australis icebreaker. Since 2011, their remains have been buried near Mawson Station.

Diana Patterson – Australia

Diana Patterson, also known as the Ice Maiden or "Lady Di of Antarctica", was the first woman to run an Australian Antarctic research station.

Diana’s Antarctic story began in 1987, when she first visited the frozen continent at Australia's Casey Station, having applied four times in eight years to join the Australian Antarctic Program. In 1989, after just one summer in Antarctica, she was entrusted to oversee Mawson Station. Her year as the head of Mawson is documented in her book The Ice Beneath My Feet: My Year in Antarctica. She later led Davis Station in 1995, and in 2002, she became the Field Leader of a conservation team working to preserve Douglas Mawson's historic huts.

Diana later became an assistant expedition leader on Antarctic cruises and commentator on Antarctic overflights. In honour of her years of dedication to the region, she was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (2013) "for service to conservation and the environment". In 2019, she earned her PhD from Monash University for her project titled "Humans and canines on the frozen continent: An examination of the relationship between explorers of the heroic era of Antarctica and their sledge dogs" - a fitting project for one of the last few people to experience dogs in Antarctica before they were withdrawn from the continent and and eventually banned in 1991.

Today, Diana is a keynote speaker who gives presentations on the challenges of leadership in Antarctica. She is currently writing a history of Heroic Era explorers and their sledge dogs.

Monika Puskeppeleit – Germany

Monika Puskeppeleit is a German doctor, researcher in polar medicine, and public health professional who made history in Antarctica as the first German medical doctor and station leader of the first all-women team to overwinter in Antarctica.

From a young age, Monika loved the winter. In a podcast interview, she recalled having the biggest sled amongst all the children she knew and using her aunt's dog to pull her in the snow. In 1979, while studying at university, Monika remembered this childhood love of winter and the snow, while watching a report on television about Americans overwintering at South Pole Station. She realised she wanted to one day do the same.

After graduating from Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Medical University in Heidelberg, Germany and becoming a doctor in 1984, Monika approached the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in hopes of joining a German overwintering team in Antarctica. She achieved her dream in 1989, becoming the first German female doctor to overwinter at the Georg-von-Neumayer Station (1989-1991).

Monika has since earned a diploma in tropical medicine and a Master of Public Health in Public Health Management and become an expedition physician in Antarctica and Mongolia with her specialised knowledge of extreme environments. As recently as the 2019-2020 tour season, she returned to Antarctica as part of an expedition team and as a scientific lecturer.

Dr. Monika Puskeppeleit, leader of the first all-women overwintering team in Antarctica. Source: Citizen Science Reisen.

Dr. Monika Puskeppeleit, leader of the first all-women overwintering team in Antarctica. Source: Citizen Science Reisen.

Janet Thomson – U.K.

Janet Thomson is a geologist who began working for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) in 1964, analysing Antarctic rock samples in laboratories in Birmingham and Cambridge. After years of hoping to "go south" like her male colleagues, she joined the U.S. Antarctic program in 1976, becoming the first British woman to conduct fieldwork on the frozen continent.

Janet later broke barriers at BAS through joining a planned geological survey that was short one man. Leaders at BAS pondered hiring a man to complete the survey, but Janet insisted that she go instead. This persistence made her the first female scientist to work with BAS in the Antarctic in 1983.

In honour of Janet’s scientific work and efforts to break gender norms in Antarctica, Peter D. Rowley of the U.S. Antarctic Research Program named a geographic feature- Thomson Summit, a peak in the Behrendt Mountains of Palmer Land- after her. Thomson Glacier on Bryan Coast is also named in her honour.

For her devotion to polar research, Janet received the prestigious BAS Fuchs Medal in 2001 and the Sovereign of the United Kingdom's Polar Medal in 2003.

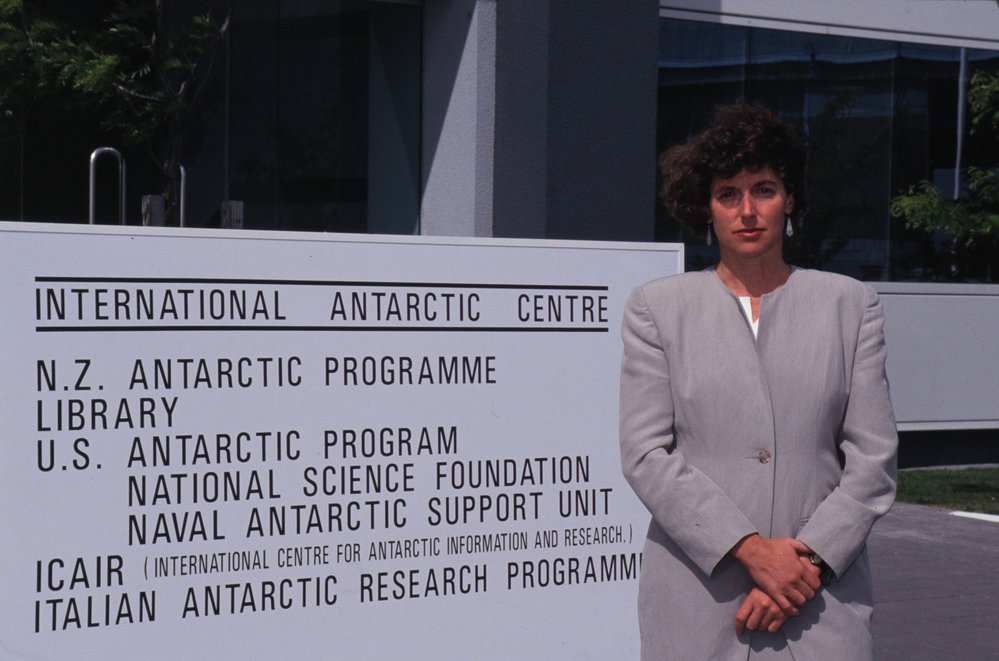

Gillian Wratt – New Zealand

Gillian Wratt is a botanist who became the first woman director of the New Zealand Antarctic Research Program (NZARP) from 1992 to 1996. She was also the first chief executive of the New Zealand Antarctic Institute, now Antarctica New Zealand, from 1996-2002.

In addition to her experience on the ice, Gillian has been Chair of the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) from 1998 to 2002 and Vice Chair of the Antarctic Treaty Committee on Environmental Protection from 1998 to 2001. Wratt went on to write a history of COMNAP titled "A story of Antarctic Co-operation: 25 Years of the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs", which was published in 2013.

Not only has Gillian done incredible work in Antarctica, but she also served as the Chief Executive of the Cawthron Institute, the largest independent non-profit science organisation in New Zealand, and the Director of New Zealand's Environmental Protection Authority. She has been the Chair of the Antarctic Science Platform Steering Group since 2018.

Gillian Wratt, former director of the New Zealand Antarctic Research Program in Christchurch New Zealand in 1993. Photo by Brian Clarke © Antarctica New Zealand Pictorial Collection ANZSC0743.18 1993

Gillian Wratt, former director of the New Zealand Antarctic Research Program in Christchurch New Zealand in 1993. Photo by Brian Clarke © Antarctica New Zealand Pictorial Collection ANZSC0743.18 1993

Conclusion

Women have and continue to contribute to our understanding of the frozen continent. By highlighting these remarkable female firsts, we honour their legacy and encourage the next generation to contribute to Antarctic science, history, and exploration.

Antarctica, with its barren but striking beauty and unpredictable conditions, remains a symbol of the world’s collective commitment to knowledge and discovery, where anyone – regardless of their gender – can make their mark.